- Trail Runner Australia

- Posts

- The science of sweat

The science of sweat

By investing just a little time and money, you can take the guesswork out of the hydration plan for your next big run.

Magic sweat machine.

There’s a lot of buzz in the running world at the moment about electrolytes and how they can help your running. But what’s less talked about is how you can take a scientific approach to your hydration to ensure you finish all your long runs in good shape.

If this is new territory for you, essentially it’s all about sweat (I wrote about this at length last week, which you can read via this link). When we sweat we lose water, plus a bunch of electroyltes, the most important of which for runners are sodium and chloride - which go together to make table salt.

A shortage of these two elements can be disastrous for the long-distance runner, potentially leading to cramps, a loss of mental acuity and an increase in blood volume which equates to a reduction in running efficiency.

Whichever way you look at it, it’s bad news.

Tech moves fast, but you're still playing catch-up?

That's exactly why 100K+ engineers working at Google, Meta, and Apple read The Code twice a week.

Here's what you get:

Curated tech news that shapes your career - Filtered from thousands of sources so you know what's coming 6 months early.

Practical resources you can use immediately - Real tutorials and tools that solve actual engineering problems.

Research papers and insights decoded - We break down complex tech so you understand what matters.

All delivered twice a week in just 2 short emails.

So, while on a long run, we need to replace both the fluid - water - and the electrolytes - sodium and chloride. But figuring out how much we need to take onboard during a long run isn’t straightforward.

This is because we all sweat at different rates. We all know people who can do a solid workout and barely break a sweat while others will look like they’ve just stepped out of a shower (spoiler: I’m in the second camp).

So the volume of sweat we lose is one variable. Another is the sodium concentration of our sweat - essentially how “salty” a sweater you are. Once you’ve nailed down those variables, you can come up with a plan to replace enough of the water, sodium and chloride you lose.

You could have a guess, but why would you when science can be your friend? If you’re prepared to invest a little time and money, you can ditch the guesswork and take a more scientific approach.

There are two variables, so it’s no surprise this is a two-step process. You need to work out the sodium concentration in your sweat, then calculate your sweat rate - the volume of sweat you lose per hour of exercise.

Feeling salty

For the first part of this process you’ll need to take a sweat test, and for this you’ll need to turn to the experts. My test was conducted by Coach Nic from Inspire Athletic in Brisbane.

I turned up for my test kitted out in all my gear, water bottle in hand, ready to work up a sweat! To my surprise, the test only required me to sit still for five or 10 minutes. Why hit the treadmill or stationary bike when the machines can do the sweating for you?

Choose Natural Relaxation Tonight, Thrive Tomorrow

CBDistillery’s expert botanist has formulated a potent blend of cannabinoids to deliver body-melting relaxation without the next-day hangover.

Enhanced Relief Gummies feature 5mg of naturally-occurring Delta-9 THC and 75mg of CBD to help your body and mind relax before bedtime. Save 25% on your first order with code HNY25.

The process of harvesting my sweat was simple and clean. Nic placed a pair of electrodes on my forearm which released a chemical that stimulated the sweat glands. A disc was placed on top of one of the electrodes. Inside the disc was a narrow plastic tube that collects the sweat.

The evocatively named “sweat collector” prior to deployment.

Both the electrodes and disc were secured to my arm tightly, meaning the sweat that was forming on my skin had nowhere to go but into the tubing, which was curled around itself in a spiral.

In my case, it didn’t take long for the tube to fill with enough sweat to move to the next step. This involved putting the collected sweat into a conductivity analyser. This measures the sweat sample’s resistance to the flow of electricity.

Electrolytes carry a positive or negative charge so the greater the concentration in the sweat, the greater the impact on conductivity. This magic machine spits out your sodium concentration in miligrams per litre of sweat.

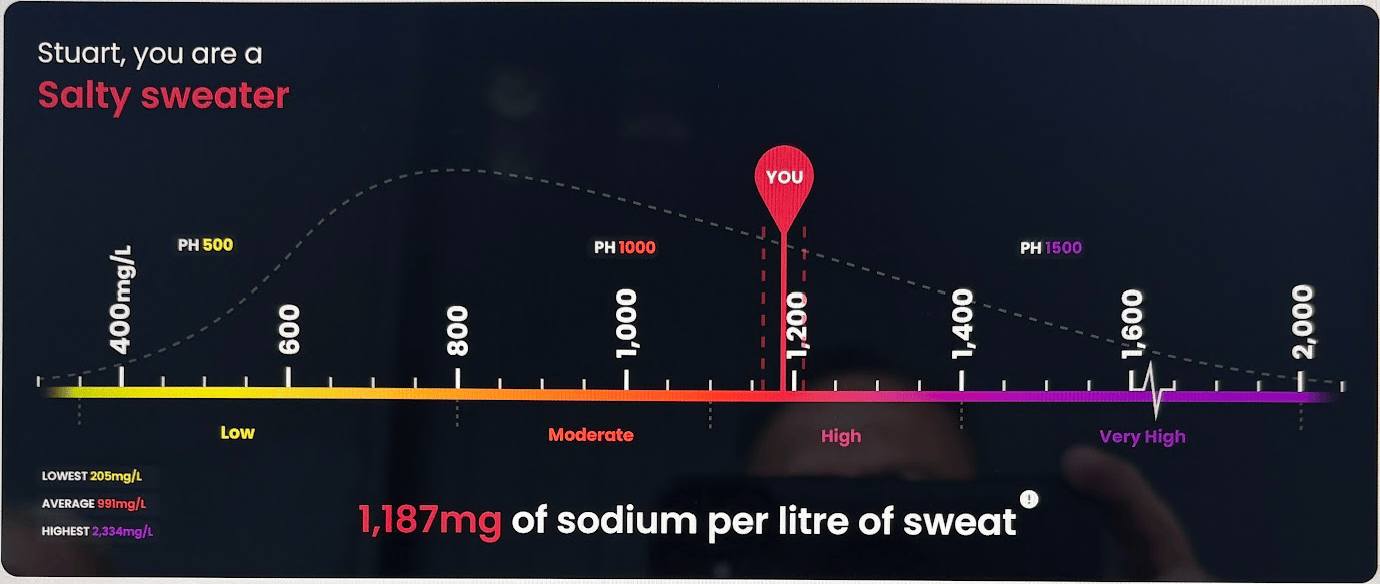

Anything under about 700mg/L is considered a low concentration, and anything above about 1,500mg/L is very high. I came in at 1,187mg/L, comfortably in the high zone on a four-point scale.

Confirmation of what I’d always suspected…

A couple of things to note about this. It’s unclear why some people are saltier sweaters than others. It seems to be down to genetics. It doesn’t seem to change much over time. Also, your body can’t manufacture sodium so you need to ingest it in some way.

Dosing up on salt the day before an event isn’t an option. Your body is always seeking to keep sodium levels in equilibrium, so if you do go down that path, all you’ll achieve is salty urine on the morning of race day.

Sweating buckets

The second part of the hydration equation, sweat rate, is something you can do at home. There are more scientific methods, but essentially you can get a good enough handle on this by measuring the amount of weight you lose during a run.

These are the steps to follow:

Figure out where you are going to run - a duration of between 45 minutes and 2 hours is the sweet spot

Go to the toilet - it’s best if you can avoid having to go during your run

Weigh yourself as close to naked as possible (let’s call this figure A)

Weigh any water bottle you are taking with you, already filled with whatever you’ll be drinking (let’s call this C)

Go for your run

When you return, strip off, towel off and weigh yourself again (let’s call this B)

Weigh your water bottle, including anything you haven’t drunk (let’s call this D)

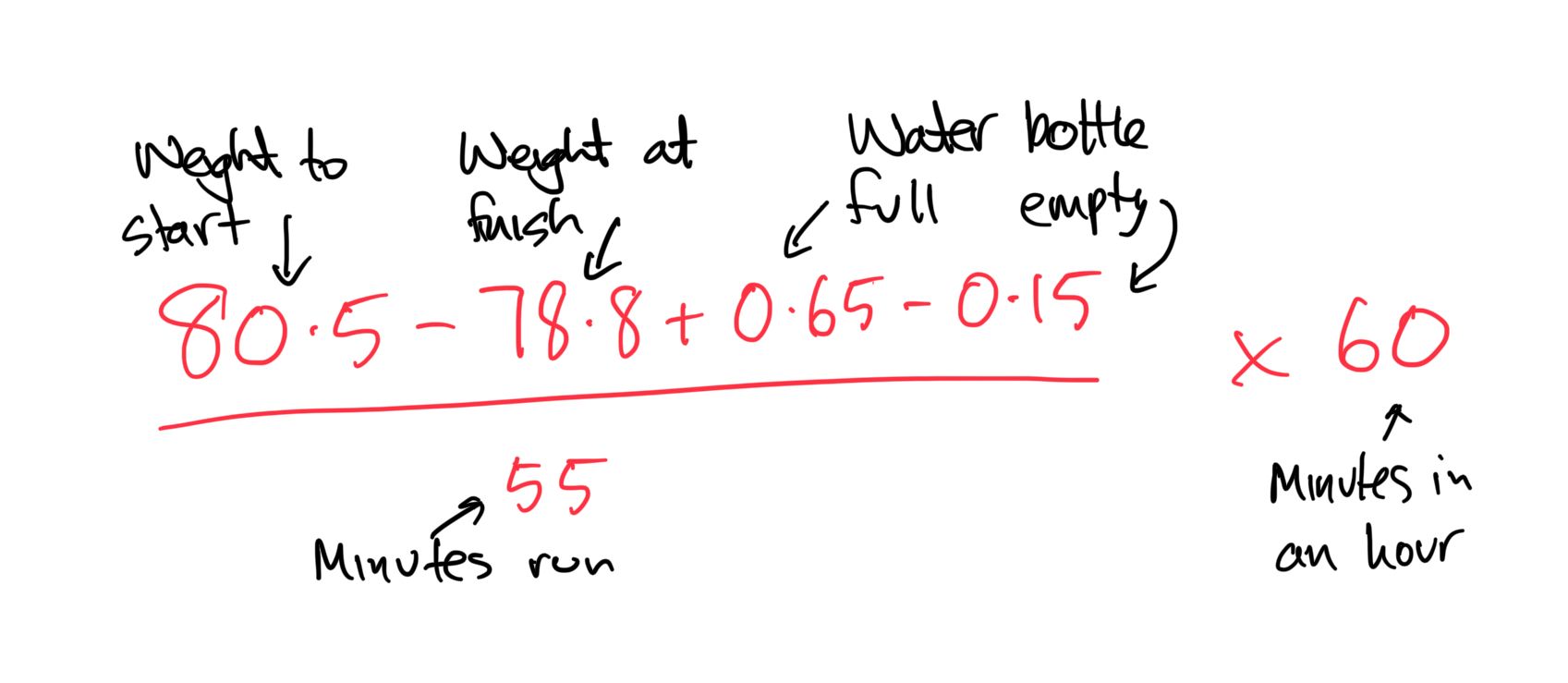

The task now is to figure out total weight prior to running, and total weight after running, taking account of any fluid you’ve taken on board during the run (noting 1 millilitre of water equals near enough to 1 gram, so 1L=1kg).

To work this out, you apply this formula: A-B + C-D. Then divide this by the number of minutes you’ve been running for, then multiply by 60. This gives you your sweat volume loss in litres per hour.

My equation.

For me, this came out at a sweat volume of 2.4 litres per hour. As expected, this means I’m a good sweater - 0.4L/hour is considered low and 3L/hour is very high.

There are some variables to consider here. Firstly, the bigger you are the more you are likely to sweat. This is because a bigger person will create more heat while exercising, so needs to sweat more to cool down.

It’s also dependent on the temperature and what you are wearing during the test. So if you are looking to replicate conditions you might find during a particular race, then it’s best to run this test in similar heat and humidity and wearing something like your race-day get-up.

So, I now know I sweat a lot, and I lose a lot of sodium in each litre of that sweat. That’s either WIN-WIN or LOSE-LOSE, depending on your framing. But it does give me the information I need to come up with a race-specific hydration plan to help me get to the end of the race without the debilitating effects of dehydration.

One final note, in researching this piece I have found the information from Precision Fuel & Hydration super helpful. The company was founded by a former elite short-course triathlete, Andy Blow, who has a degree in Sport and Exercise Science.

Their website is chock-full of really interesting information and tools to help you in the hydration and fuelling space. They also have a range of great explainers on their YouTube channel.

The test I did, with Coach Nic from Aspire Athletic, was a Precision Fuel and Hydration test.

Upcoming Events

There are way too many events for me to list everything that’s happening around the country, but here is a selection of upcoming races (with a bias towards South East Queensland).

Event | Location | Date |

|---|---|---|

Kosciuszko National Park, NSW | 14 February 2026 | |

Mt Buller, Vic | 20 February 2026 | |

Wilson’s Promontory, Vic | 21 February 2026 | |

Mt Baw Baw, Vic | 1 March 2026 | |

Glenview, Qld | 1 March 2026 | |

Warburton, Vic | 7-9 March 2026 | |

Gold Coast, Qld | 13 March 2026 | |

Katoomba, NSW | 14 March 2026 | |

Brisbane, Qld | 15 March 2026 | |

Noosa, Qld | 21 March 2026 |

The Running Calendar website is a great source if you want a comprehensive understanding of what’s available around Australia.